Apps may detect a maximum of 10% COVID-19 infections, according to a study by the UPC’s BIOCOM-SC group

A multidisciplinary team

The research team consists of Daniel López-Codina, Sergio Alonso, David Conesa and Enric Álvarez, from the UPC’s Computational Biology and Complex Systems Group (BIOCOM-SC), and Martí Català and Pere-Joan Cardona, from the Comparative Medicine and Bioimage Centre of Catalonia of the Germans Trias i Pujol Research Institute (CMCiB-IGTP), under the coordination of Clara Prats (BIOCOM-SC / CMCiB-IGTP).

A study conducted by the UPC’s Computational Biology and Complex Systems Group (BIOCOM-SC) reveals that Bluetooth-based apps are able to detect a maximum of 10% of infections. The study reports that apps could help detect some cases but they are under no circumstances the main tool for fighting the virus. According to the research team, primary attention and public health services are the most suitable to trace the potentially infected contacts that a person has had after testing positive for COVID-19 by conducting direct interviews.

Jul 31, 2020

Over the last weeks, many countries have been using apps for digital contact tracing. The percentage of use of these applications is different in each country: from 15% in Germany to almost 40% in Iceland, a small and high-tech country. In France it is much lower: few people have trusted the application and less than 4% have downloaded it.

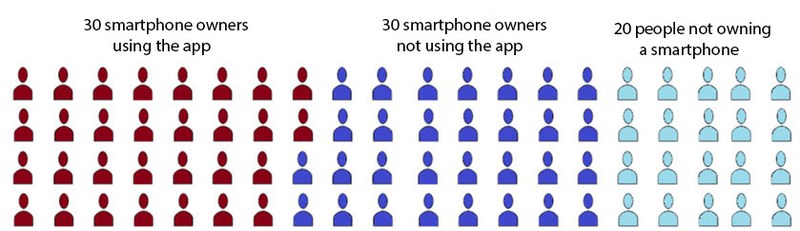

According to Sergio Alonso, a researcher from the Computational Biology and Complex Systems Group (BIOCOM-SC) of the Universitat Politècnica de Catalunya · BarcelonaTech (UPC) and the coordinator of the study, “the penetration of smartphones in Spain is now 75%. This means that 1 in 4 people do not own an Internet-connected phone. Children and the elderly are a significant percentage of people who do not typically own a smartphone and who are unfortunately also affected by the pandemic.”

Moreover, not everyone who owns a smartphone is willing to download the app. 80% of smartphone users download and use the most popular social media apps. But many people are reluctant to give access to their phone. In addition, many users keep their Bluetooth and GPS off. There is no guarantee of such a percentage, says Alonso: “A survey conducted in Germany revealed that approximately 50% of people would not install a COVID-19 contact tracing app for such reasons.”

The study shows that, in the most favourable scenario—assuming that half of smartphone owners installed it—35% of people would have the app installed and running. The minimum requirement for an infection to be detected is that the two people have the app installed: this means that the app could detect an infection in approximately 12% of cases (the result of multiplying 35% by 35%) in the best possible scenario, implying that the app worked perfectly and detected all possible sources of infection.

This figure is far from herd immunity, which would mean detecting and isolating 66% of the contacts of the infected person. According to the study, an effect equivalent to herd immunity could be achieved if 80% of the people used the app and immediately self-isolated after a contact who tested positive for COVID-19 was identified. But the potential use of these apps is very far from such figures, so stopping the spread of the virus cannot rely on them exclusively.

Let's consider a group of 80 people. One of them is infected and has had close contact for 15 minutes with another individual. What is the probability of identifying the contact with the app? 30 out of 80 is the probability that the infected individual owns a smartphone and uses the app; 29 out of 80 is the probability that the person they had contact with also owns a smartphone and uses the app, that is . If the app works perfectly, only 13.5% of contacts can be identified.

A large percentage of contacts would go undetected

Unfortunately, apps cannot identify 100% of infections between users because they are based on algorithms that can register contact between users when they come within 2 metres of each other and for more than 15 minutes, or similar. Many potential cases can be detected so, but some cannot. Enric Álvarez, one of the co-authors of the study, explains that “virus transmission occurs mainly in indoor spaces with poor ventilation (droplets are not removed) or air conditioning systems that do not work properly (droplets are constantly in motion). For example, it is more dangerous being five metres from a COVID-19 infected individual in a poorly ventilated bar than being one metre from them in a cinema. No cases of mass infection have been reported in cinemas or theatres, but many in pubs and parties. Indoor settings lead to a number of infection cases, even when people stand relatively apart.”

The study estimates 70% of relevant cases are related to close contact and thus can be detected by apps, which would not be able to detect the remaining 30%. The latter could instead be detected by a more traditional tracing system, that is direct interviews with patients. Thus, based on the fact that apps can only identify two thirds of infections and the little estimated use of such apps, the study concludes that only a maximum of 5–10% of all possible infections would be detected.

In the most optimistic scenario, in which more than 50% of smartphone owners downloaded the app—and not the estimated 35%—or in which undetected cases not related to close contact were less than 30%, apps could reach a detection rate of 15–20%. However, in a less favourable and more realistic scenario, in which less than 50% installed the app, the detection rate would drop to 1–5%.

“Such figures could rise if apps could detect whether the user is indoors or in a poorly ventilated space. But this is hard to achieve with today’s technology. Not to mention the privacy issues that should be addressed for using personal data”, concludes Alonso.

According to the research team, apps could help detect some cases but they cannot be the main tool for fighting the spread of the virus. Primary attention and public health services are the most suitable to trace the potentially infected contacts that a person has had after testing positive by conducting direct interviews. Daniel López-Codina, another of the co-authors of the study, says: “It is a priority to increase human resources in primary attention and public health services, apps cannot replace them in any way.”